Format: eBook, 30 pages (PDF)

Genre: Poetry

Publisher: Poets in Nigeria (January 1, 2019)

Reviewer: Adedayo Adeyemi Agarau

This is how you enter a review: you pray that you survive the tormenting imagery of the book you are wading past, that you do not sink in the ocean of alphabets clustering as deep metaphors in this sermon. So, I begin in the name of the father, the newly damned and in the broken wings of dying birds.

Pamilerin Jacob’s poems explore the creative backends of very taunting places like mental health. It is not a safe house, not a healing city, his themes are his infirmities really. 29 pages, 17 poems. 17 hurting, sorrowful works. One must have thought that the author of the gospel intentionally wanted to becloud the earth with darkness. However, in spite of the tone that spreads across the book, each poem carries the affirmation of reality, the borderline amongst depression, mental health, and stigma.

Pamilerin, who unlike the meaning of this pseudo-name, broke my spirit in the opening poem. Genealogy (of Stigma) opened with the usage of “&” to effect polysyndeton:

& Ignorance begat Insecurity & Insecurity begat Shame & Shame begat Fear

&…

Poetry is in its simplest form in that line. How Pamilerin reassures and reinstates in total confidence the entirety of the flowchart of mental bully. Isn’t that what this book is about? How the process begins and how the body becomes home with this social castigation for the mental state and of course, the repelling, that is, the body protesting against the obvious. Olawale, who is fondly known as Pamilerin Jacobs, is the man, I must confess: He is the voice piece of the damned, no matter the time proximity. This book opened me up and filled my body with bullets of truths. Isn’t that what poetry is supposed to do–, sort out the truth from an array of metaphors and then feed you till your body finds peace?

Although we cannot neglect the comics that come with the harsh reality of the world we live in, we must laugh about…

a therapist organizing

deliverance sessions

Although I will rather not give this book a title as limiting as a gospel, the poet justifies his reasons at several points in this book:

Zion s p r e a d e t h forth her hands

& there is none to comfort her

- Lamentations 1:17

& there came a leper to him, beseeching him, & kneeling down to him, & saying unto him, if thou wilt, thou canst make me clean

- Mark 1:40

…the voice of one CRYing in the wilderness

– John 1:23

We must all together agree that Pamilerin, whose work questions and probes the borderlines of religion in relationship with belief surrounding mental health, is knowledgeable about both parties.

In First Miracle or the First Attempt at Preaching to a Knife, Pamilerin explores the concept of will. If thou wilst… he recounts the leper’s experience with Jesus, the son of man who played a super intellectual game on the “compassionate miracle worker.” However, the will seemed to be at home in that poem, according to Pamilerin Jacobs.

if thou wilt…

I scratch my eyes with a knife

& light changes colour

The constant occurrence of the clause, if thou wilt…, refers the reader back to the fact that suicide, amidst other factors surrounding Mental health, sits solely on the power of the underlying will trapped in the body. This can be seen when the persona scratches their eyes with a knife under the if thou wilt…

The body is an active party, usually affected, when there is a mental breakdown. Usually, cankerworms begin to eat the heart deeply, then motivates the fingers to rise, to take a knife, to cut the skin, cut the skin… Pamilerin must have written this gospel in a cathedral of memories while sitting on the pew of its pain.

On several accounts, Pamilerin attempted:

enticing the body with silence

and he succeeded. This is probably because of the sincerity of the flow, the huskiness of the energy from which the poems come. His themes ranged from mental illness to stigma to misconceptions to loss to suicide. He, however, didn’t limit the work to blandness, he carved a niche for himself through this short collection by exploring structural landscapes. A typical example is the stigma “justification” survey on pg.11. The survey, as it appeared came brief, shocking and breathtaking.

A video which made rounds on the Nigerian social media space had a woman, whose communication skill had a broken body, spear people who commit suicide. She came with the belief that they were selfish, stupid and even worse. I agreed that she knew so less about mental health, but a colleague, whose cousin drank Sniper retorted with the same belief. I am made to believe that in the face of great pain, or in the context of loss, we crucify the shadows of the ones brave enough to leave, brave enough to bleed…to death.

Pamilerin has carved a popular class for his writing on Instagram, and he is a young and buoyant voice to reckon with in the Contemporary Nigerian Writosphere. And I believe that writing poetry is more intentional. Very intentional. This statement does not overlook the fact that there are cases of bad writing that are dashing into the streets in recent time. Irregular and repelling metaphors are weaved in the chase for a strong content which leaves the reader lost and helpless. Jacob, however, in Luminous Mystery 04: Trans-disfiguration proved a point that he is not from that lineage. therapist: on a scale of 1-10, how strong is the impulse to cut?

patient: I suck at measuring / but I can tell you for sure / the blade has a voice / soft as tissue paper / has a smile / that slices my skin / without my consent

At each level, the poet recounts with metaphors how therapists are unable to relate with the deep dark place where mental illness cuts from. And he points to the therapist, the society as the ones who shackle people in darkness. This leaves the reader wondering how. I wondered for a while too. But of course, the obvious is the stigma that comes with mental illness is almost as the one moulded HIV/AIDS.

Flirting with the Scriptures in few poems in the collection, Pamilerin retold the story. Better. The gospel is meant to guide readers and if Jesus would read this, The Lore of the Fig Tree would teach him to have been softer with the fig tree:

his saviour does not curse him

for having scars instead of fruits

In Self Portrait as an Eternal Wound, the spirit of the book didn’t stop growing. The poet breathes out itself the same way death outgrows the body. In this book, there are no bad poems, no poem is out of place or prodigal.

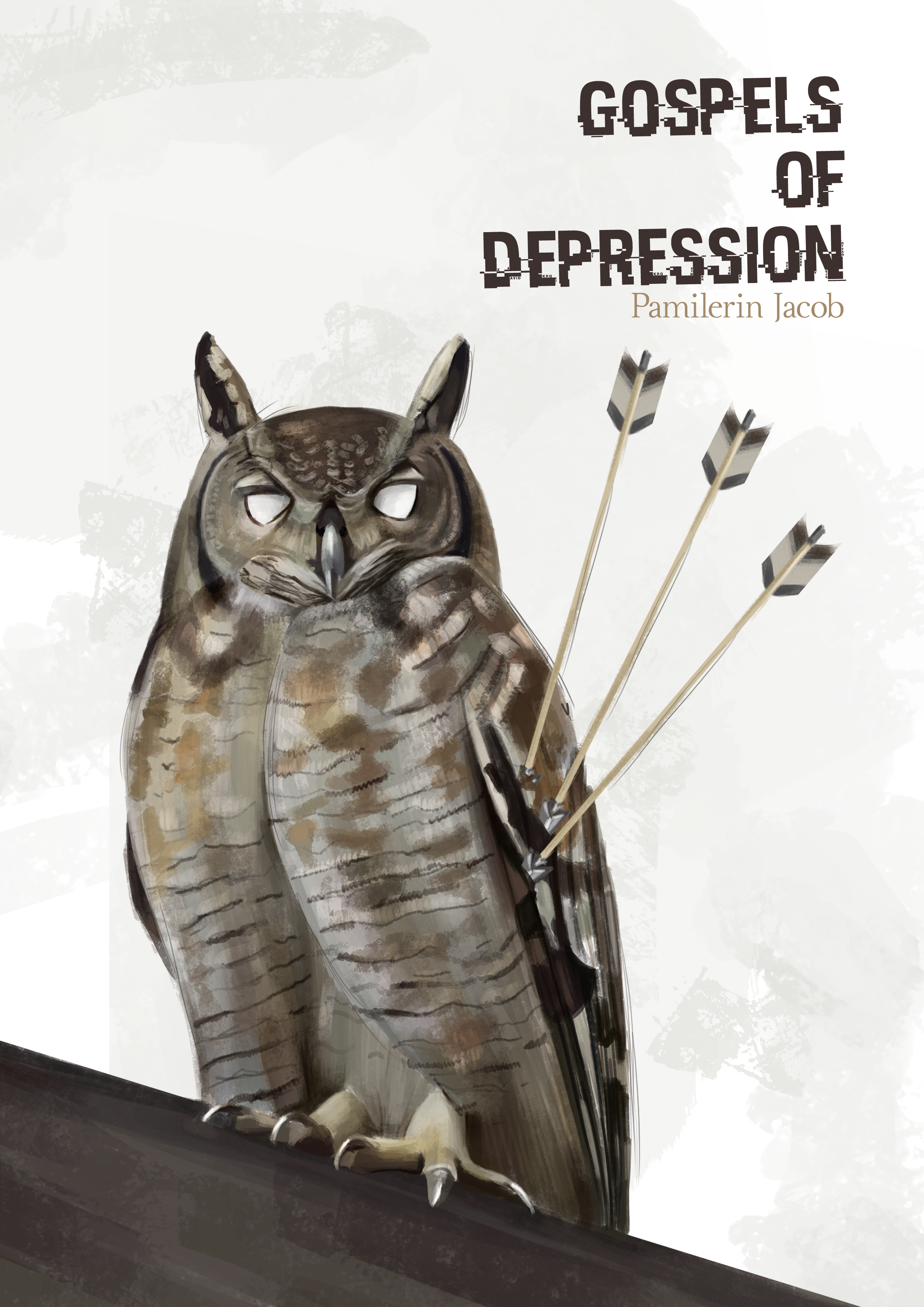

I, however, believe that this book is the Gospel of Depression ACCORDING to Pamilerin Jacob. The gospel is a text reserved widely for personal perspectives and stories. I have taken this book as a guide, a light to see me through the dark in this light. The creative team of the Poets In Nigeria made massive impression using this book; the layout, cover design and the general production is quite commendable.

In the end, will you be strong enough to dare point your middle fingers at every misconception about mental health? Will you be the table shaker, the one who breaks every leg of the table or the one that falls with that Olympus? Pamilerin has set a creative trend, a platform to build your voice on, will you amplify and change how we care for ourselves and mental health?

DOWNLOAD GOSPELS OF DEPRESSION HERE.

ADEDAYO AGARAU, Author of For Boys Who Went, is a Nigerian documentary photographer and poet. He explores the concept of godhood, boyhood, distance, and absence. His works have been featured on Gaze Mag, Allegro, Obra Artifact, Constellate, Jalada Africa, Geometry, 8poems, BarnHouse, Barren Magazine and elsewhere. His chapbook, Asylum Chapel, is forthcoming from Pen and Anvil Press, Boston. His poem, Stones, made the shortlist of Babishai Niwe Poetry Prize in 2018. He won the first prize of PIN Food Poetry Contest (2015) with his poem, “For You, Dear Home”.

ADEDAYO AGARAU, Author of For Boys Who Went, is a Nigerian documentary photographer and poet. He explores the concept of godhood, boyhood, distance, and absence. His works have been featured on Gaze Mag, Allegro, Obra Artifact, Constellate, Jalada Africa, Geometry, 8poems, BarnHouse, Barren Magazine and elsewhere. His chapbook, Asylum Chapel, is forthcoming from Pen and Anvil Press, Boston. His poem, Stones, made the shortlist of Babishai Niwe Poetry Prize in 2018. He won the first prize of PIN Food Poetry Contest (2015) with his poem, “For You, Dear Home”.